MINNEAPOLIS – Children growing up in the Watford City area who resisted their chores were sometimes met with a haunting motivation.

“For that area of North Dakota, a lot of people were told this story as a cautionary tale,” says Charles Griak, film director. “‘If you don’t do your chores, Charles Bannon is going to get you.’”

The stern warning would be a dire prompt to the youngsters, who’d heard of the serial murderer who once worked as a hired hand for a family of five from the area, the Haven family, whom he killed on their farm in 1931.

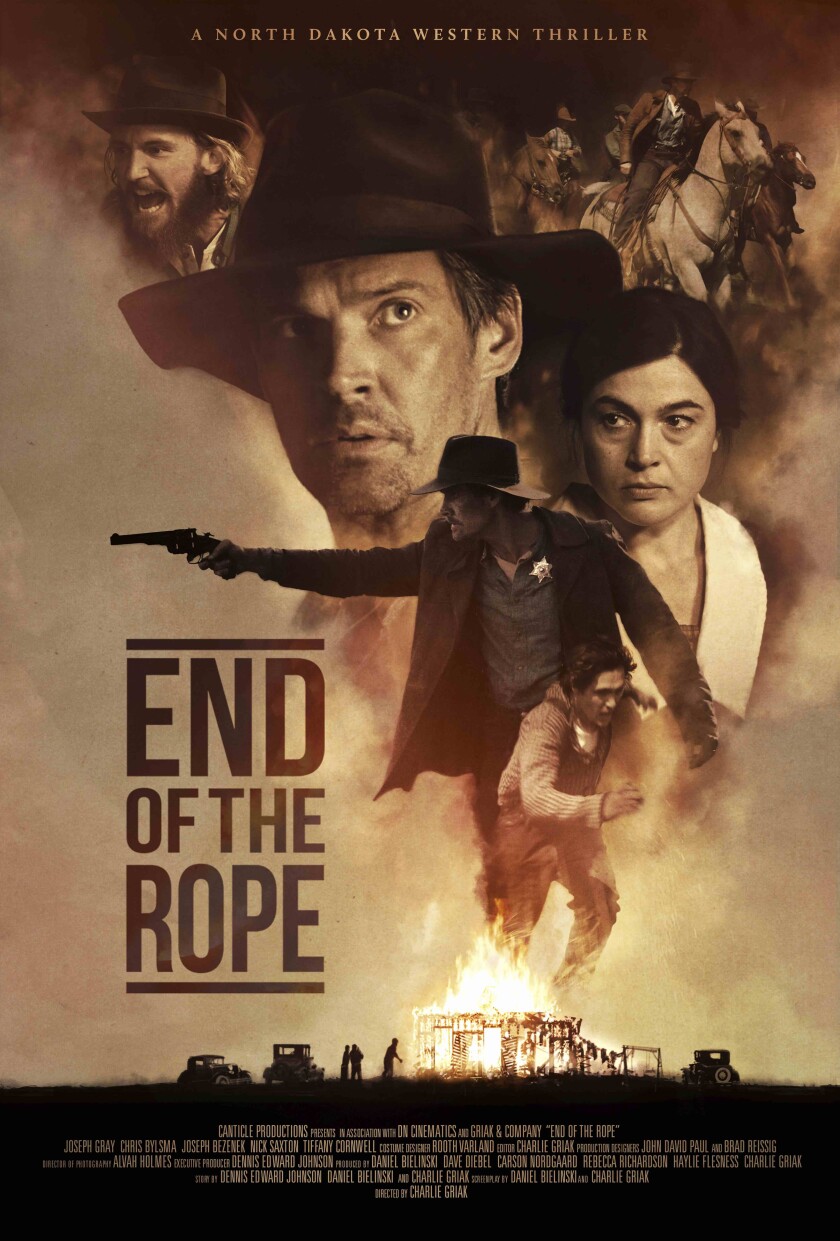

Griak directed the film, “End of the Rope,” by Canticle Productions, which will premiere in Fargo in a week, and is based on that tragic event and the mob lynching of Bannon that followed at Cherry Creek Bridge in western North Dakota. The movie was patterned after Dennis E. Johnson’s 2009 book, “ End of the Rope: The True Story of North Dakota’s Last Lynching .”

Griak recalls the day producer Dan Bielinski approached him about directing the film. “I still have the grainy photocopies he sent me of the articles about this story,” along with Johnson’s book. “When I read the story, it felt like it was made to be a movie. There are so many exciting twists and turns.”

He also has a connection to the area, with his mother being a Bismarck native. “Growing up, I spent a lot of time there. I remember driving with my parents through the Badlands. It’s such a beautiful area.”

Having directed Canticle’s first film, “A Heart Like Water,” also filmed here, Griak was eager to return for another round.

A relatable tale

Most of the filming took place in Watford City, North Dakota, near Schafer, where the murders occurred.

“The amount of help we received from the people of North Dakota was unbelievable,” Griak says, with much of it donated. A construction team “essentially built this main street to replicate 1930,” while many from the area offered their antique cars.

The town had a vested interest in seeing the story told, he notes, with some taking part as background actors.

“I love that Dan is telling stories of the history (in North Dakota),” he says, adding that at one point, Schafer could only be reached by boat. The isolation meant that “things developed in a unique way. They had to deal with this situation on their own.”

Johnson was part of the collaboration of shaping the film, but unfortunately, died not long after the filming in 2021, Griak says. “He really wanted this to happen. Dennis was a big driving force in it all. He put a lot of work not only into the movie, but also the book. It was an important creation for him.”

Griak says the story, though having taken place decades ago, is very relatable. “This was a smaller town than most of us live in right now, but they still had all of the types of conflicts and troubles that the modern world has.”

The film, he adds, is essentially about a community trying to figure out what to do in a difficult situation. “We present it from a lot of different perspectives and angles, and as much as this was a tragic story, we try to bring some light into it as well.”

Lives instantly changed

Lead actress Tiffany Cornwell plays Sarah Jacobson, “a woman whose life changes in an instant, and she is consumed by that moment.”

Though a woman in the 1930s who doesn’t have a lot of power, Sarah, she says, feels the need to take some kind of action. Her husband, the sheriff, has different ideas about how to handle things.

Cornwell says that in the real story, a fire killed the couple and their three young daughters, and “their burned bodies were found huddled together, terrified, in the basement.” The woman whose character formed the basis of Sarah, it’s been told, “would be found wandering around saying prayers, crying out for them,” the rest of her life.

Though the mob that lynched Bannon, whose identities were never found, were all male, the hooded masks they wore were sewn by machines likely handled by women, she notes. “So, there’s historical evidence to say women were involved as well.”

It became important “to give voice to a mother’s experience, to the lives and stories of the women in the town who may have lost their best friend, who felt powerless, and used what they had to try to find justice.”

In playing the role, “Everything inside of me became heavy, like molten lava, and crowded by grief,” Cornwell says. But she threw herself into the part willingly, seeking to honor the stories of “the women who have struggled to find ways to survive tragedy with dignity and justice.”

She was especially touched to realize the connection the story had to the people surrounding them. “It’s visceral when you drive into town and sit at the gravesites of the people whose stories you’re telling. It becomes more real.” https://36ada7343b1aa71c1a36a091a61d231d.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html

Frontier justice vs. the law

Joseph Gray came all the way from Greensboro, North Carolina, to lead in the film. “I absolutely loved (North Dakota). It’s beautiful up there,” he says. “I love the outdoors, love riding horses, and love the beauty of the landscape.”

He plays CA Johnson, the sheriff. “I think what most attracted me to him was the conflict of him wanting to do what was right in spite of his own desires and what the popular thing to do was.”

In contrast, “A lot of the townspeople want frontier justice, not justice by the letter of the law. Some might even call it vengeance.”

To step into the part, especially of someone in “a fairly dark place—he’s been through a lot more than I have,” Gray worked to “winnow away” the parts of himself externally that couldn’t connect to do so internally, “by imagining circumstances where I might be struggling with, if not the same things, then similar things.”

Like Cornwell, he found the role exhausting. “My character was heavy-laden. He was burdened. But I dug in and leaned in and just allowed myself to be tired for a month.”

“We shot some of the scenes where they happened, like the Old Schafer Jail where they were holding Bannon,” he adds, noting, “They did a great job of paying homage to Westerns, but in a Western-type thriller style.”

Gray, a Christian, says the role had him reflecting on pride, and how we are warned about it in Scripture. “It’s still our problem today, and it manifests in so many different ways,” he says. “We might seek to be inflated, and when we’re not, we can get deflated and depressed.”

Relating again to the story, he says, the Bible also cautions us “about the heart being deceitful.” “As much as I love the Disney stuff, you can’t just follow your heart,” he remarks. “You’ve got to lead your heart.”

Ultimately, the film offers the kind of conflict that often shows up as extreme situations in film, TV and books, but is “scalable,” he says, and applicable to our everyday situations.

“It’s a compelling story, it’s captivating and engaging, it’s relatable, and it’s based on a true story—with some creative liberties taken,” Gray says.

Cornwell, who also acted in Canticle’s previous two productions, including “Sanctified,” which premiered last fall, says “End of the Rope” encompasses both a larger cast and production value.

“Good stories are worth an evening of your time,” she says, encouraging moviegoers to see the film. “This is a good, based-on-a-true story that is important for people to know, and will leave you asking a lot of questions about yourself.”

IF YOU GO:

What: “End of the Rope” film premiere and red-carpet event; Q&A with filmmakers and actors

When: 7 p.m., Friday, March 31

Where: Fargo Theatre, 314 Broadway, Fargo

Contact: Tickets, $20, at https://www.endoftheropefilm.com/ (tickets) or email tickets@canticle-productions.com .

[For the sake of having a repository for my newspaper columns and articles, I reprint them here, with permission, a week after their run date. The preceding ran in The Forum newspaper on March 24, 2023.]

Leave a Reply